Bloody Nile Watercolor and Solzhenitsyn on Art

Why do art? And how does one get inspiration? For the first question, I will quote Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn at the end of this post. For the second, I will describe the process of how I created this watercolor.

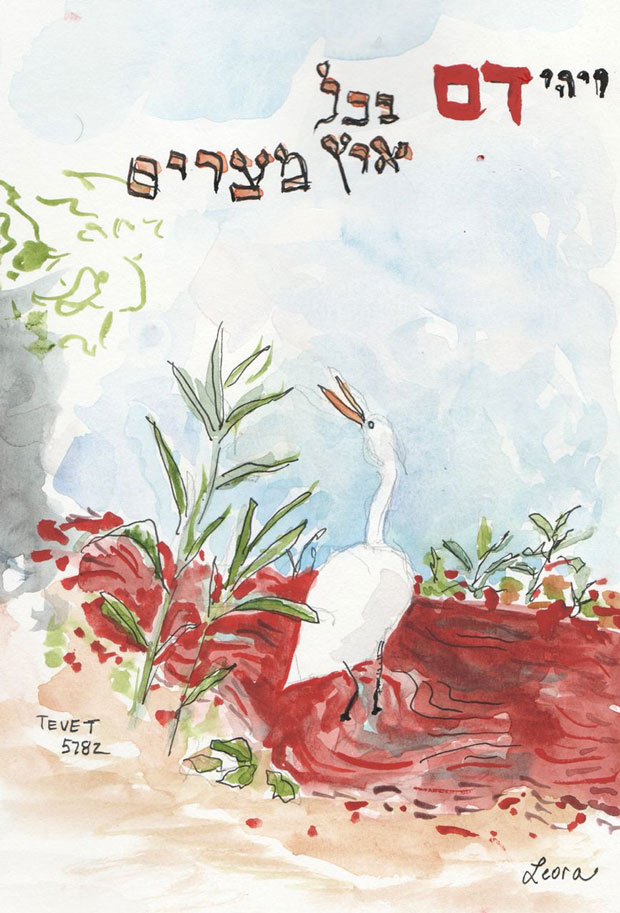

I painted this watercolor in response to reading about Plague Number One: blood. How does one depict a bloody river Nile? A while back, I painted a dull straight river of blood. I wanted something more watery. I looked at paintings of Winslow Homer and J.M.W. Turner. Both are known for their water scenes. I happened upon a small museum book of Japanese paintings that belonged to my mother z”l. The covered showed an egret (at first, I thought it was a stork — I need to improve my birdwatching skills) bathing in a body of water. Actually, there are two egrets in the scene. I just focused on the right side. The reeds kind of look as how I would imagine greens growing next to the Nile might look. And my friend later told me indeed egrets are found in Egypt.

When I do biblical art, I recently started adding a snippet from a pasuk (a phrase of Torah) to the side of the art. Here is another version of this painting, one that cites the plague of blood:

Parshat Vaera, Shmot 7:21 “and the blood was throughout all the land of Egypt.”

Quotes from Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s 1970 Nobel Lecture

Who was Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn? Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was born in 1918 in Kislovodsk, Russia. In 1945 he was arrested for criticising Stalin in private correspondence and sentenced to an eight-year term in a labour camp, to be followed by permanent internal exile. The experience of the camps provided him with raw material for One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, which he was permitted to publish in 1962. In 1970 he gave a lecture upon receiving the Nobel prize, and the main topic was art.

Not everything can be named. Some things draw us beyond words. Art can warm even a chilled and sunless soul to an exalted experience. Through art we occasionally receive–indistinctly, briefly–revelations the likes of which cannot be achieved by rational thought.

Later in the lecture:

But who will reconcile these scales of values and how? Who is going to give mankind a single system of evaluation for evil deeds and for good ones, for unbearable things and for tolerable ones–as we differentiate them today? Who will elucidate for mankind what really is burdensome and unbearable and merely chafes the skin due to its proximity? Who will direct anger toward that which is more fearsome rather than toward that which is closer at hand? Who could convey this understanding across the barriers of his own human experience? Who could impress upon a sluggish and obstinate human being someone else’s far off sorrows and joys, who could give him an insight into magnitude of events and into delusions which he has never himself experienced? Propaganda, coercion, and scientific proof are equally powerless here. But fortunately there does exist a means to this end in the world! It is art. It is literature.

Source: The Solzhenitsyn Reader, edited by Edward E. Ericson, Jr. and Daniel J. Mahoney